Craig Dykstra saw things afresh

The longtime Lilly Endowment vice president’s impact is felt in the hospitable spaces he cultivated, the disciplined reflection he nurtured, and the ripple effects of a life well lived.

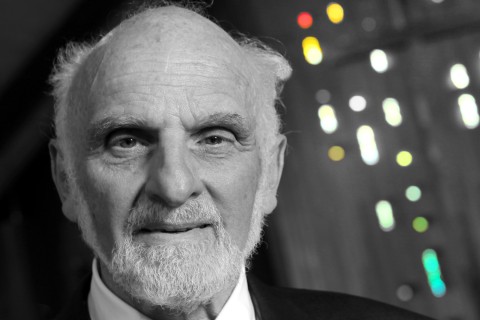

Craig Dykstra (courtesy of Duke Divinity School)

It is rare to meet someone whose words, leadership, and life cohere as beautifully as they did in Craig Dykstra, who died this week. Craig was an early proponent of the importance of “vision and character,” and he wrote a book with that title. He was focused on “growing in the life of faith,” the title of another of his books. Along the way his emphasis on vision became oriented toward imagination, specifically pastoral imagination, and his emphasis on character and its formation became centered on the importance of Christian practices. He helped others, and especially those of us who knew him, see things afresh.

Craig spent much of his life developing his ideas in and through administrative leadership, especially as vice president for religion at the Lilly Endowment. In that work he emphasized the importance of creating “hospitable spaces for disciplined reflection,” and he did so, drawing ever larger communities into the orbit of relationships and networks cultivated by the endowment.

Throughout his life Craig embodied convictions, drawn from his Reformed Christian commitments, rooted in the awe and wonder of God and the beauty of God’s grace. He loved the poetry of Denise Levertov, especially her poem “The Avowal” and its image of a “free fall” into floating in God’s “all-surrounding grace.”

Craig’s academic interests and religious convictions found their heart in his love for congregations, the ecclesia. One of the hallmarks of his leadership was his investment in congregations and other institutions and their pastors and leaders. He didn’t just care about pastoral imagination; he had the heart and sensibilities of a pastor, and he encouraged pastors regularly and well.

To know Craig wasn’t just a matter of learning about the importance of vision and imagination, character formation and the beauty of Christian practices, the awe and wonder of God and the centrality of grace, the significance of congregations and institutions. It was to encounter someone whose life shone through those commitments—a creative pastor and teacher with the exceptional gifts of an administrative leader. His impact is felt in the hospitable spaces he cultivated, the disciplined reflection he nurtured, and the ripple effects of a life well lived.

I first met Craig in the early 1990s. I was a young academic, and I got an invitation from Craig and Dorothy Bass, his longtime collaborator and friend, to come to a meeting in Indianapolis to discuss the significance of Christian practices. My dissertation had looked at Alasdair MacIntyre’s understanding of practices in relation to formation, and so I happily accepted the invitation. Little did I know the impact that meeting would have on my life. It began a journey of new patterns of thinking, new frameworks for my vocation, and lifelong friendship with Craig (and many others). I am a different and better person because of Craig, a sentiment that countless others share.

Craig’s life had the heartbeat of a midwesterner shaped by Reformed faith. Born and raised in Michigan in the Reformed Church of America, he was ordained as a Presbyterian. He studied philosophy at the University of Michigan, attended seminary at Princeton Theological Seminary, and then, after a year serving as a pastor in Michigan, returned to Princeton Seminary for his PhD work in Christian education. He brought his undergraduate interests in philosophy to his doctoral work, becoming part of the first wave of a renewed interest in virtue and character led by scholars such as MacIntyre, Iris Murdoch, and Stanley Hauerwas.

Craig taught for several years at Louisville Presbyterian Seminary and then at Princeton before joining the Lilly Endowment in 1989. He served at the endowment for what he later called “23 glorious years” before leaving in 2012 to join the faculty at Duke Divinity School. He continued working with the endowment as a board member. He retired from Duke in 2020.

Craig and his beloved wife Betsy were married for 56 years. They had two sons, Peter and Andrew, and Craig loved to talk about his sons, daughters in law, and grandchildren. Indeed, Craig’s lifelong passion for the centrality of vision and character came to life most vividly in his love for young people, from the youngest of children through young adulthood.

Craig’s most lasting legacy is his transformative leadership at the endowment across those 23 years. He built on the distinguished legacy of his predecessors such as Bob Lynn, bringing his intellectual vision, pastoral heart, and administrative savvy to bear in charting exciting new possibilities for the intersections of faith and philanthropy. His leadership at Lilly was transformative for many congregations, institutions, pastors, and scholars. The impact of his leadership centers on three themes I have already identified: his hospitable spaces, his frameworks for disciplined reflection, and his emphasis on relationships and networks.

Craig began creating hospitable spaces as a teacher at Louisville and Princeton, and he brought that spirit with him to the endowment. The group on Christian practices that he and Bass convened met for several years, culminating in the book Practicing Our Faith, which they co-edited. That book became a launchpad for other working groups and the eventual publication of a wide variety of resources, including books on specific practices as well as edited volumes on the importance of practices for congregations, Christian life, and theological education.

Perhaps Craig’s most innovative and transformative leadership, though, came in his development of major initiatives to nurture hospitable spaces within and across grant projects. As Lilly’s grantmaking portfolio grew, Craig and the religion division developed requests for proposals for grant programs that could both seed projects for congregations and pastors, youth, church-related colleges, and seminaries and cultivate hospitable spaces for reflection within and across them. Across the country, new hospitable spaces emerged.

There was an underlying framework that animated these major initiatives: each initiative was the result of disciplined reflection to frame creative approaches. Craig’s emphasis on shared Christian practices and his focus on imagination led to painstaking work on how to encourage vocation, support and sustain pastoral excellence for the sake of vibrant congregations, and cultivate a more transformative approach to strengthening institutions through Christian leadership.

I was privileged to work with Craig on framing some of these initiatives. I marveled, and sometimes chafed, at his disciplined reflection and the earnestness with which he approached any task. I remember times when I thought the framing was good enough, and Craig would insist that we weren’t there yet. In part this was the philosopher in him, wanting to be as disciplined as possible in our use of words. It was also because he believed the stakes were very high. He wanted to be sure that these initiatives were framed in ways that would enable participants to apprehend and embody, through practice and reflection, the redemptive activity of God. That is worth a lot of disciplined reflection.

At the heart of Craig’s administrative leadership and his work as a teacher and scholar was a deep appreciation for the formative significance of relationships. He was a superb listener and a faithful friend. He delighted in the presence of others, and he genuinely sought the good for those with whom he worked, those whom Lilly served, and all those who came across his path. He embodied grace and encouraged imagination. I always knew that a conversation with Craig, whether in person or on the phone, would begin with personal and theological reflection before we got to the work at hand. Indeed such reflection was always a part of the work at hand.

Craig consistently was on the lookout for signs of grace and love and joy. His interest in vision, going back to his study of Murdoch’s work in the 1970s, and later his emphasis on imagination were both about seeing—and especially seeing the goodness, the mystery, the wonder of God and of each person, congregation, and organization in the light of God. When Craig would point to favorite biblical passages or tell stories about his favorite novels or movies or grant convenings, he invariably would talk about seeing others, the world, and especially God afresh. He would often describe the disciples on the road to Emmaus, where in their practice of hospitality they discovered a profound gift that preceded, and reshaped, their practice: the gift of the risen Christ and a new way of seeing. In Levertov’s words, Craig knew that “no effort earns that all-surrounding grace.”

One of the most difficult conversations I had with Craig was in the second meeting of the practices group. I hardly knew him, other than as a senior scholar and leader whom I admired. I had just finished describing to the group what I thought was an insightful set of critiques of American culture and mainline Protestantism. A break followed shortly thereafter, and Craig pulled me aside. He told me that “narratives of declension and critique” were too easy and that they led people down paths of passivity and discouragement. The whole focus on Christian practices was to be oriented in a more positive direction. I was quite unhappy at the time with his comments. I thought he was being a bit of a Pollyanna, not wanting to see the truth of what I saw.

Yet Craig’s words were deeply pastoral, and across time they have reoriented my life, my thinking and writing, and my leadership. I slowly discovered that Craig was neither Pollyannish nor simply an optimist. His focus on the future, his emphasis on grace, his commitment to creating hospitable spaces for disciplined reflection, and his deep care for friendship and vocation all reflected an abiding sense of awe, wonder, and delight in the mystery of God. He grew in the life of faith throughout his journey, and he enabled me and many others to discover and see afresh the grace, love, joy, and wonder that shine through the resurrected Christ. May he rest in peace and rise in glory as he sees God afresh.